Proteins are composed of monomers called peptides and polypeptides. This blog will answer questions like what are the monomers of proteins that are relevant to students and teachers. We will also discuss factors affecting protein formation; the difference between protein types such as globular, fibrous, membrane, and nuclear proteins; regulation of protein synthesis at transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational levels and more particularly on what are the monomers of proteins.

The monomers of proteins are called amino acids

Amino acids have a central carbon atom with four different groups attached to it. These groups are:

- A carboxyl group (COOH), which is an acidic functional group that can be used as a hydrogen bond acceptor.

- An amino group (NH2), which is an acidic functional group that can be used as a hydrogen bond donor.

- An alpha-amino group (NH2), which is a basic functional group that can be used as a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor.

- A side chain, which is not involved in forming bonds between amino acids, but instead plays a role in determining the properties of each type of amino acid.

Proteins are long, chain-like molecules composed of repeating subunits called monomers

Protein monomers are the building blocks of proteins. A protein is a long, chain-like molecule composed of repeating subunits called monomers, which are joined by chemical bonds called peptide bonds. Proteins perform many important functions in living organisms, from acting as enzymes to providing structural components.

Proteins have four different types of monomers: amino acids, dipeptides, tripeptides and oligopeptides (polymers). Amino acids are the smallest units of protein and make up 75 percent of all proteins found in nature. The remaining 25 percent are dipeptides and tripeptides. Oligopeptides can also be considered polymers.

The structure of each monomer is unique with each amino acid having its own chemical properties like hydrogen bonding abilities or hydrophobic interactions with other amino acids or water molecules.

There are 20 different monomers of proteins

These monomers differ from each other by an amino group and a carboxyl group attached to the same carbon atom. The exact order in which these monomers are linked together is what makes each protein unique.

Protein monomers can be divided into two categories: essential and non-essential amino acids. Essential amino acids are those that cannot be synthesized by the body, so they must be obtained from dietary sources. Non-essential amino acids can be made by the body without the help of dietary sources.

Proteins are made up of chains of monomer units called amino acids

Amino acids are small molecules that contain an amine group (NH2), a carboxyl group (COOH), and a side chain. The side chains vary greatly in size and shape, but they all have one thing in common: they contain hydrogen atoms.

There are twenty different amino acids found in proteins, each with its own unique set of properties. For example, some amino acids are positively charged at neutral pH (lysine), while others are negatively charged (aspartic acid). Some amino acids contain sulfur atoms (cysteine) or nitrogen atoms (asparagine).

Proteins are built out of monomers

There are 20 different types of amino acids that occur naturally in our body, 12 of which are essential and cannot be produced by the body. Each protein is made up of a sequence of these 20 different amino acids, linked together in a specific order.

The sequence of amino acids in a protein determines its function and shape, as well as any interactions it may have with other molecules in the cell. For example, the protein hemoglobin contains four chains, each made up of 141 amino acids arranged in a certain order.

Depolymerization reactions

The monomers of proteins are amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins. The number of possible combinations of amino acids is huge — according to one calculation, there are 12 amino acids and 20 different ways that each can combine with other amino acids.

Some of those combinations are not functional because they don’t form a stable structure, or because they have a negative effect on the organism. But many others do form stable structures that perform specific functions in the cell.

Amino acids make up proteins

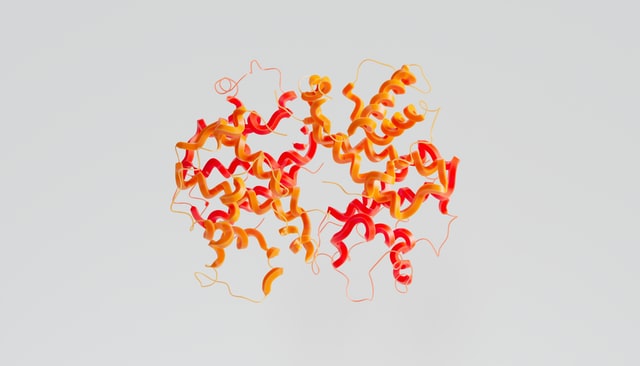

Amino acids are small molecules that link together to form long chains called polypeptides. These polypeptides fold into a specific three-dimensional shape. This folding is what gives proteins their unique characteristics.

There are 20 different amino acids found in nature that can be linked together to form proteins. These amino acids have different chemical properties based on their structure and charge:

- Hydrophobic amino acids — These amino acids repel water and are hydrophobic, so they tend to be found on the inside of a protein’s structure, where they don’t interact with water and other polar molecules in the body.

- Polar amino acids — These amino acids attract water and tend to interact with other polar molecules in the body.

A single amino acid is a monomer of a protein

The first step in the synthesis of proteins is the formation of a peptide bond between two amino acids to form dipeptides. This process requires ATP energy and the enzyme aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase.

The process continues by adding more dipeptides to form oligopeptides; this process requires energy from GTP. The next step is the formation of polypeptides, which involves joining together a series of oligopeptides. Polypeptides are made from monomers linked together by amide bonds between the carboxyl group (-COOH) of one amino acid and the amine group (-NH 2) of another amino acid through dehydration synthesis or condensation reaction.

Conclusion

Amino acids are the monomers of proteins, which are essential to all living things as they make up the structures in cells and perform all of life’s functions. There are twenty different amino acids that mix and match together to create countless combinations of proteins to meet the needs of the body. The amino acids determine the shape of a protein, which becomes a part of the cell.